I am really surprised by the amount of people that don’t know where Black History Month comes from. Let’s be real, I was one of them! I guess we have been so conditioned with conspiracy theories, that we all think the white man gave us the shortest and coldest month of the year to degrade us, but really this couldn’t be farther from the truth.

Carter G Woodson, also known as, The Father of Black History is the person who initiated the first steps to what we now know as Black History Month.

Woodson was one of 9 children to his father James Woodson and mother, Anne Eliza. James was a Civil War veteran who learned carpentry from his father and earned money laying foundations for homes. His family owned a poor six-acre farm, mostly farming vegetables, that he worked on. His father, James, was illiterate, but he made sure he taught Carter basic principles of life. He refused to hire out his children to gain any kind of income for the family. Woodson said that his father “[b]elieved that such a life was more honorable than to serve one as a menial.”

Have you ever heard of the McGuffey Readers? It was one of the first textbooks in America that was made to become progressively more challenging with each volume. This was what Woodson was reading when he got the bright idea that he wanted to be like one of the successful characters in the book, and go to college.

He graduated high school in 1896 and then received the equivalent of a two-year degree at Berea College and that same year he graduated, in 1903. Woodson also visited the Philippines and became a supervisor of a school program. There, he realized that Filipinos were not being taught about themselves and their history and he saw the similarities with African Americans. He witnessed very clearly that Black people weren’t being taught enough about their own achievements. Woodson graduated with a Bachelors and a Masters Degree in History from the University of Chicago and became the second African American to receive a PhD at the university.

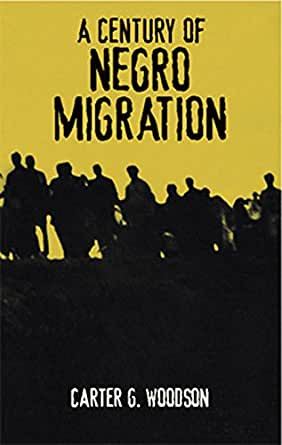

In 1918, Woodson published his book, A Century of Negro Migration, which argued that the Great Migration represented a “new phase of Negro American life which will doubtless prove to be the most significant event in our local history since the Civil War.” This book famously put Carter on the map, and less than a decade later, he established Negro History Week. Carter Woodson believed that when whites realized that African Americans made more than enough contributions to this world, that racial discrimination wouldn’t be so bad.

This crusade is much more important than the anti-lynching movement,

because there would be no lynching if it did not start in the schoolroom.

— Carter G. Woodson

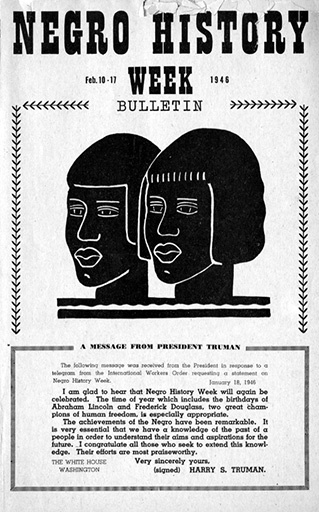

In February 7, 1926, Woodson initiated the first celebration of ,Negro History Week. Woodson chose February for Negro History Week for reasons of tradition and reform. The week he chose was symbolic because it was the same week of the birthdays of former President Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave and prominent abolitionist movement activist. In his eyes, these were two great Americans who played a huge role in Black History. More importantly, Woodson believed that history was made by the people. He envisioned the study and celebration of the Negro as a race, not solely as the producers of great men. Woodson wanted to continue commemorating the achievements of African Americans separate from agitation and the political side, saying “Lincoln, however great, had not freed slaves – the Union Army, including hundreds of thousands of Black soldiers and sailors, had done that.”

Why shouldn’t we focus on the people that contributed to the advance of human civilization?

Negro History week appeared across the country in schools and before the public. It is said that the 1920’s was the decade of the New Negro, a name given to the post-World War I generation because of its rising racial pride and consciousness. The Black middle class became participants and consumers of Black literature and culture. Black history clubs were on the rise and teachers demanded materials to teach students. Developing whites, even stepped up and endorsed the efforts.

The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (still around today) and Woodson set a theme for the annual celebration, and provided study materials—pictures, lessons for teachers, plays for historical performances, and posters of important dates and people. As the Black populations grew, mayors issued Negro History Week proclamations, and in cities like Syracuse, developing whites teamed up with Negro History and National Brotherhood Week.

Woodson’s home state of West Virginia, began to celebrate February as Negro History Month. Frederick H. Hammaurabi (a cultural activist) started celebrating Negro History Month in the mid 1960’s. He used his cultural center, the House of Knowledge, and his African background to combine African consciousness with the study of the Black past.

In 1976, ASALH used its influence to institutionalize making Negro History a full month instead of just a week. Around the 50th anniversary of Negro History Week in the 1970s, Gerald Ford was the first President to issue a national Black History Month proclamation and every U.S. President since has issued proclamations endorsing the ASALH’s annual theme and so here it is.

Black History Month.

Now, as we continue to celebrate this historical month, let’s remember where it came from and why. We must continue to celebrate and educate Black History and our achievements as Woodson wanted us to. Recognize and support that small business your Black neighbor has started or the nonprofit to help Black students. It is important to realize that this month is not only for us, but also BY US.

Powered by WPeMatico