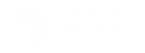

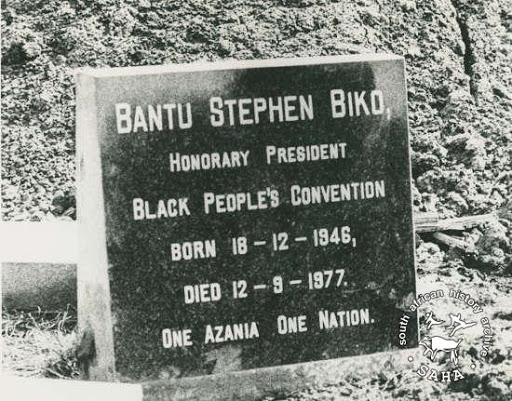

On September 12, 1977, intellectual, activist and founder of South Africa’s Black Consciousness Movement – Bantu Stephen Biko, commonly known as Steve Biko – died in the empty cell of Pretoria Central Prison.

His death shocked the world but his legacy undeniably changed the future of Black liberation and human rights.

A child of three, Biko was born on December 18, 1946 to Mathew Mzingaye and Alice Nokuzola Biko. Registered to the University of Natal’s Black Section in Durban, Biko was a registered student of medicine but quickly flourished into a spokesperson for Black emancipation.

Biko’s political career began harmlessly, with his admission into the Student’s Representative Council (SRC). It was 1967 when Biko attended the annual conference led by the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) at Rhodes University.

The NUSAS were sympathetic to the anti-apartheid movement and the demands of Black South African students however, Biko quickly realized that the members were mainly white and did not really seem to tackle the root issues uniquely faced by Black South Africans.

When the host of the conference banned mixed raced accommodation, this was a clear sign for Biko. He believed that a Black-led group was essential for Black equality, so the following year he, with the support of mainly Natal students, created and presided over the South African Student Organization (SASO).

SASO, which is currently running, was to later grow influence across the country, publicly opposing the apartheid and impacting movements such as the revolutionary Soweto student uprising in 1976.

Unlike NUSAS, the group was not open to white South African’s as Biko and the members believed that the liberation of Black men and women was a responsibility by and for Black people.

“The fact that the whole ideology centers around non-white students as a group might make a few people to believe that the organization is racially inclined,” he said during a presidential speech in 1969.

“We have a responsibility not only to ourselves but also to the society from which we spring. No one else will ever take the challenge up until we, of our own accord, accept the inevitable fact that ultimately the leadership of the non-white peoples in this country rests with us.”

After one year as president, Biko was elected chairman of SASO Publications and began publishing articles under the pseudonym Frank Talk titled ‘I write what I like’. His articles, which covered an array of topics challenged the education, political and social systems that grossly disadvantaged Black people in South Africa. His growing influence and writings gave him an opportunity to also share what he believed was the core of this dilemma: the Black consciousness.

For Biko the Black man was “a shell, a shadow of man, completely defeated, drowning in his own misery, a slave, an ox bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity.” Black Consciousness was an inward process of understanding identity, Biko wanted to channel the anger and frustrations of Black people into something they could all fight for.

His two pillars for this ideology were:

- Being Black is not a matter of pigmentation – being Black is a reflection of a mental attitude and;

- Merely by describing yourself as Black, you have started on a road towards emancipation, you have committed yourself to fight against all forces that seek to use your Blackness as a stamp that marks you out as a subservient being.

For Biko, there would be no fair and accurate articulation of the Black struggle if the Black person did not see themselves separate to the destructive image imposed by others – particularly, oppressive white-led systems and laws.

Known for phrases such as “Black man you are your own” and “the most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed” he publicly defined Black as beautiful.

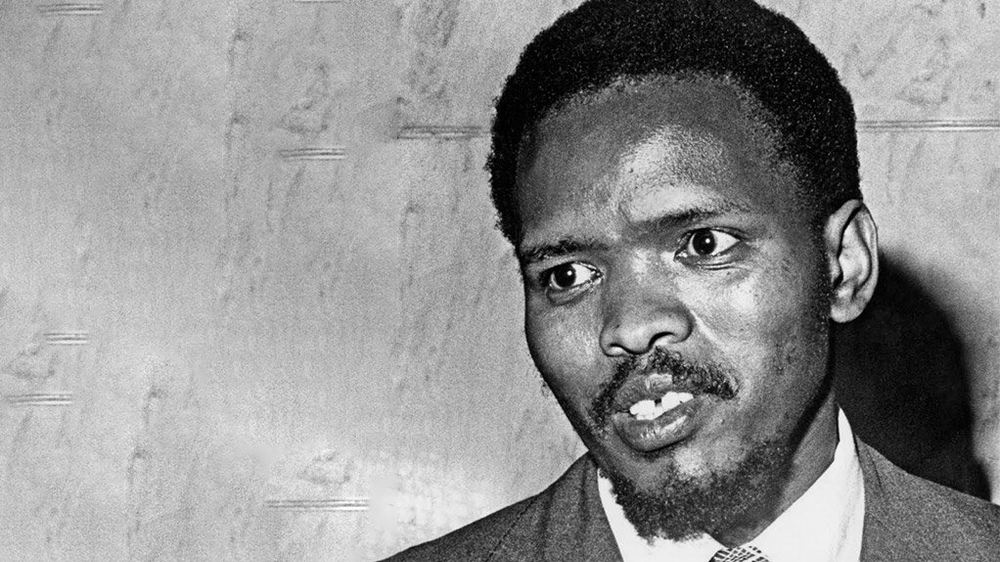

Due to the work of Biko and the SASO, groups such as the Black People’s Convention (1972) and the Zimele Trust Fund (1975) which supported political prisoners and their families were created. He also continued the Ginsberg Trust to support Black students and under the SASO founded the Black Worker’s Project (BWP).

In 1970 he married Nontsikelelo Mashalaba and two years later was expelled from university, joining the Black Community Program (BCP) as a branch executive. Biko visited universities, corresponded with political activists and wrote to keynote foreign representatives. Viewed by the eyes of the government as a threat, he was continuously detained and banned.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6U6s83k4KPo

On August, 18 1977 Biko and colleague Peter Cyril Jones were arrested outside of King William’s Town.

In the same year, SASO and other pro-Black organizations were banned and formally labeled as illegal organizations.

Sent to the notorious Port Elizabeth’s security branch, Biko was severely tortured sustaining a brain hemorrhage. Naked and placed at the back of a land rover, he was forced to make a 12-hour-journey to Pretoria Central Prison on September 11, 1977. He died the following day.

Police later told Biko’s family that he was on a hunger strike but independent investigations saw the true story pursued by his followers. Drawing international attention, despite the castration of national political movements in South Africa itself, Biko’s death was instrumental in uncovering abuses of human rights.

Before his death, Biko was interviewed by The New Republic where he described a recent interaction with a police officer who would not readily beat him after he was detained.

“You see the one problem this guy had with me: he couldn’t really fight with me because it meant he must hit back, like a man,” he said.

“So I said to them, ‘Listen, if you guys want to do this your way, you have got to handcuff me and bind my feet together, so that I can’t respond. If you allow me to respond, I’m certainly going to respond. And I’m afraid you may have to kill me in the process even if it’s not your intention.'”

Despite an inquest in 1980 surrounding his death, it was only in 1997 – 20 years after his death – in which a confession was submitted by the officers who had killed him.

Steve Biko has received the Atlanta Freedom of the City Award (1997), Presidential Awards (2002) and the PACON Posthumous Pan African Icon Award (2012).

Mariam Koslay is a journalist, creative and community member based in Melbourne, Australia. You can follow her on Instagram via @mariamkoslay.

Powered by WPeMatico