A woman holds the ends of her skirt, coyly twirling away from the man dancing opposite her. The couple is dancing Rumba, more specifically, a version of Rumba called guaguancó. The energy is sensual, fast-paced, with twists and turns accompanied by the constant drum beats and percussion. Rumba in Cuba has flourished and come to be known as one of the signature dances from Cuba. Its history is an example of how music and dance adapt to include changes in culture and politics. The rhythms, an expression of identity that connects with communities. Music and dance can help us trace this history, and in this article, we will be looking at Rumba from Cuba, and Champeta from Columbia.

Rumba emerged from the ‘solares’ in parts of Matanzas and Havana. The solares were where the newly freed slaves lived once slavery was abolished in Cuba in 1886. The name itself can be derived from the name for a party or festival, and whole streets would come alive with dance and music which is an example of what the rumba dance symbolizes. It was a way for the marginalized community to express themselves, to dance, to be free, and to have a sense of community. Rumba is a personification of the African and Spanish influence on Cuba. In a journal titled,‘Race, Gender, and Class embodied in Cuba’ by Yvonne Payne Daniel, the components of Rumba are described.

“The Spanish influence is the vocal stylization, song structure, and language. African contribution is displayed in the call and response patterns, inclined and flexed postures, manner of instruments, emphasis on torso- generated movement and isolation of body parts”.

Photo credits :Flickr

The instruments used in Rumba are an indication of the history of the dance. There are three major congo drums that create the infectious beat. The first is quinto, which is the highest-pitched. Second, tres dos, which are middle-pitched, and tumba/salidor, which is the lowest-pitched. Other instruments include claves, which are two wooden sticks that are struck against each other, shakers, bells, and catá /guagua. Rumba is also used to describe a complex of related Cuban dances including Guaguancó, Yambú, and Columbia.

Guaguancó is one of the most commonly known forms of Rumba and is a couples dance. The vibe of the dance is sensual, where the man attempts to woo the woman while the woman resists his attempts. Yambú is not as sensual, the tempo slows down and is still a popular form of Rumba to dance to. Columbia is traditionally danced by men and is a sort of competition where the men show off their different dance moves.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E5ysX2Jbebg

Champeta, compared to Rumba is relatively new as it initially emerged in the 1970s from Cartagena de India and Barranquilla on the coast of Colombia. The Pacific and Caribbean coast has the highest population of Afro-Colombians. Like Rumba, however, Champeta came from a place of creating an identity and outlet for a marginalized community. Champeta evolved in the 1970s when a lot of sailors would bring in African tapes, and these tapes would spread through the communities. Artists such as Fela Kuti, Miriam Makeba, and Lokassa Yambongo were extremely popular. It was not only music from Africa that was coming in. Zouk from Martinique & Guadeloupe, Soca from Trinidad & Tobago, and Reggae & Dancehall from Jamaica were also coming in and spreading like wildfire. One of the main reasons for its spread and the molding of Champeta is Picós. Picós were large, mobile, craft sound systems that were like street clubs. Picós were extremely popular as it was a place people could listen to good music and not have to spend a lot of money.

According to an article titled ‘Champeta Music: Assertiveness of the Afro-Colombian People’, the name champeta is said to come from the men who were day workers and would come to listen to the newest songs from the Picós. The article states “[t]he imported African music was essentially consumed by the lower Black classes. Many of the socio-economically disadvantaged men of Cartagena used to work at the Bazurto market and other manual labor locations in Cartagena. The Bazurto is the biggest market in Cartagena and due to its location, almost functions as a division between the upper-class Cartagena and ʻthe otherʼ Cartagena with its barrios populares and a great share of African-descendant population. These men used to carry a medium-sized knife with them, called champa or champeta. Soon, the listeners of this music began depreciatively to be called champetúos and their music champeta.”

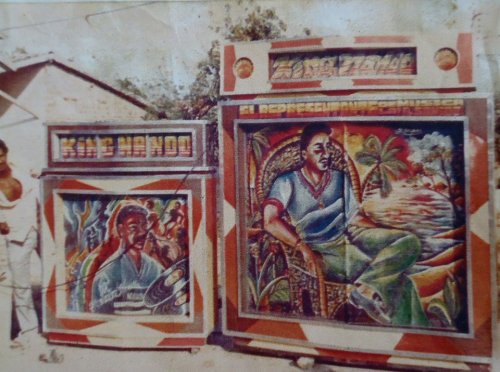

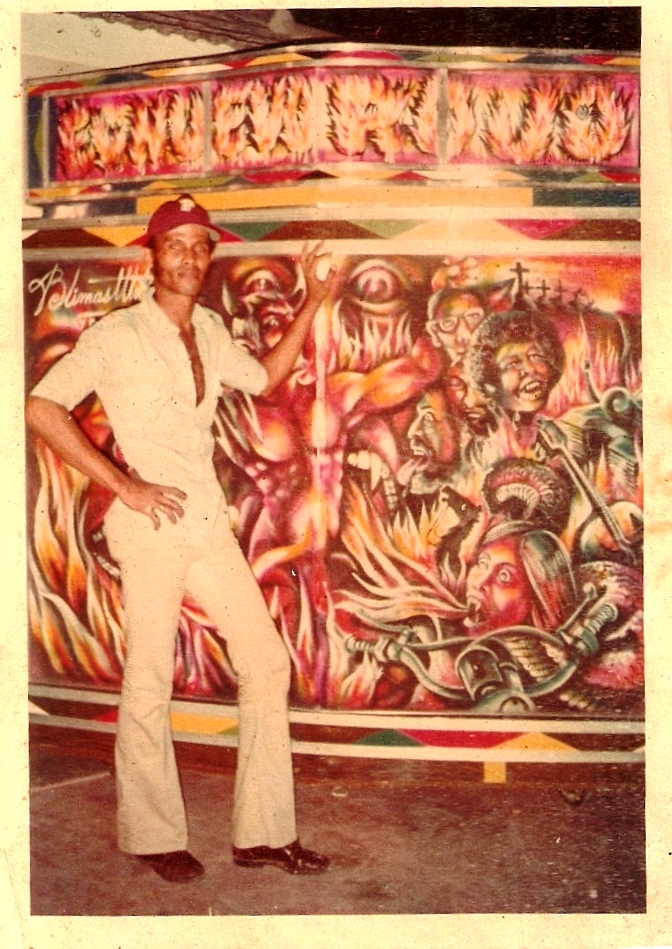

Vintage Picós from the 80’s. Photo credit: Fabian Altahona Romero, Blog Africolombia

While these tracks that were flowing into Cartagena and Barranquilla were still not ‘Champeta,’ picós were a huge factor in its development as they would take some of the most popular songs and remix them to fit the audience. Picós would compete with each other and try to build a following by having the latest mixes that no one else had. Songs such as ‘Shakara’ by Fela Kuti became Shakaloa and was a huge hit. Despite the music being popular in the different neighborhoods, it was still not being played on the radios or even accepted by the larger Colombian population. Champeta was considered to be vulgar and rebellious as the lyrics often spoke of more than just having a good time. Lyrics would point out politics, social problems, exclusion, and demands for change. Charles King who is considered as one of the forefathers of Champeta uses his music to talk about love, and having a good time while also reflecting on his everyday reality. As a result, Champeta artists initially found it difficult to get radios to agree to play their songs. Champeta, however, has slowly made its way from out of the shadows and is a growing genre in Colombia.

Both Rumba and Champeta are an example of how music and dance were used to overcome and celebrate culture and identity.

Powered by WPeMatico