When you think of which country was never colonized in Africa, you probably think of Ethiopia. However, Liberia is also known to be the West African counterpart that was never colonized. While Liberia was never technically colonized by way of imperial annexation as took place in the rest of Africa, it‘s foundational story has an intriguing echo of colonization. A movement to send freed slaves back to Africa was the fuel behind the creation of Liberia. The question is who started it, and were their intentions pure?

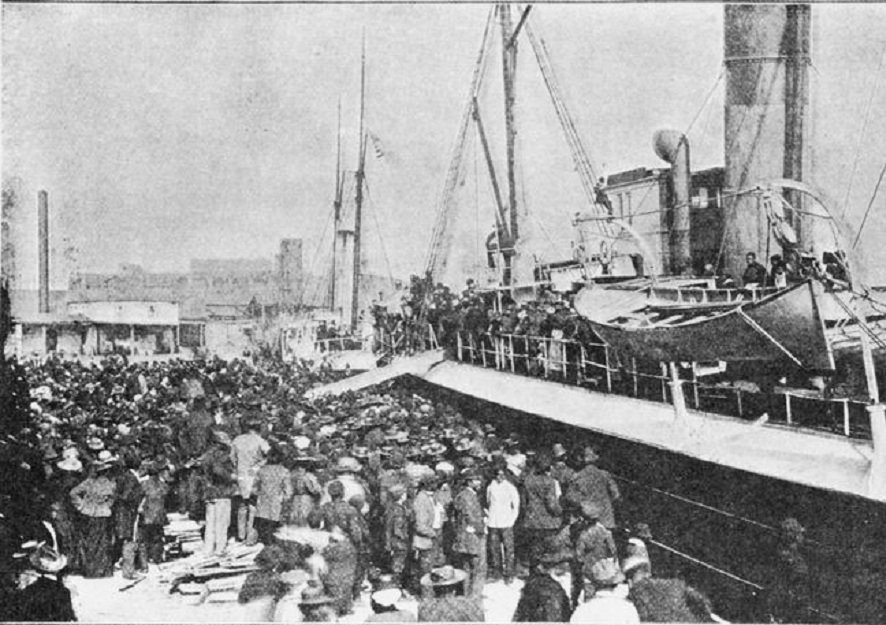

The biggest question facing the leaders of the United States in the early 19th century was what to do about slavery. The question to continue, or to abolish and what to do with freed Black people if slavery ended was on the forefront of the country’s mind. Many white people at this time thought the solution was to send free Black Americans to Africa through “colonization.” Introducing the American Colonization Society (ACS), the private company that sought to create a colony for this very purpose, had mixed motives. Over the next three decades, the society would secure land and ship freed Black Americans to the colony, which would become the nation of Liberia.

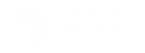

In 1817, in Washington D.C., the ACS established the new colony on a plot of land in West Africa they had purchased from local tribes. Their hope was that slaves, once emancipated, would move there. The society, which was Quaker-oriented but also consisted of some slave holders, preferred this option to a growing number of free Black Americans demanding rights, jobs, and resources in America. It was in 1822 that the first 86 of thousands of former slaves sailed from the New York harbor to their new home in West Africa. The ACS called the land Liberia, and between 1821 and 1840 about 20,000 former slaves, fugitive slaves, freeborn Africans from the New World and Europe, as well as recaptures (illegally enslaved Africans freed by British naval courts) came to live in Liberia through the ACS initiative.The different sections of returnees came to be known as Americo-Liberians, having been grouped under the umbrella of the first and majority group of returnees from the United States. This group also included the children of white-and-Black relationships.

Photo: Departure of free African Americans to Liberia (Face 2 Face Africa)

Notable supporters of transporting freed Black people to Liberia were Henry Clay, Francis Scott Key, Bushrod Washington, and the architect of the U.S. Capitol, William Thornton. All were slave owners. Considered to be “moderates” of the time, they believed slavery was unsustainable and should eventually end, but they did not consider integrating slaves into society as a feasible option. The ACS in turn encouraged slaveholders to offer freedom on the condition that those who accepted would move to Liberia at the society’s expense, and many slave owners took that option.

When the settlers were first relocated to Liberia, the plan attracted immediate criticism from many sources. Leaders in the black community publicly attacked it, posing the question why free Black people should have to emigrate from the country where they, their parents, and even their grandparents were born. On the other hand, slave owners in the South vehemently opposed the plan and declared it an assault on their slave economy.

Photo: The New York Chapter of the Colonization Society (The New York Historical Society/Getty Images)

Abolitionist resistance to colonization steadily grew. In 1832, as the ACS began to send agents to England to raise funds for what they advertised as a benevolent plan, William Lloyd Garrison fired up the opposition with a 236-page book on the evils of colonization and sent abolitionists to England to track down and counter ACS supporters. Nevertheless there were some fans of the plan. Slave states like Maryland and Virginia were home to a large number of free Black people. While people there, still reeling from Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion in which emancipated slaves had a hand in, formed local colonization societies. As a result, Maryland legislators passed a law in 1832 that required any slave freed after that date to leave the state, and specifically offered passage to a part of Liberia which was administered by the Maryland State Colonization Society. However, the new mandate lacked strong enforcement and many Marylanders forgot their aversion towards free Black people when they needed extra hands at harvest time.

By the 1840s, the American Colonization Society was largely bankrupt, and the transported Liberians were demoralized by hostile local tribes, bad management, and deadly diseases. The U.S. government declined to claim sovereignty over the colony so the ACS demanded that Liberians declare their independence. In 1847 Liberia gained independence from the ACS and drew up a constitution and elected its first president, an Americo-Liberian named Jospeh Jenkins Roberts. The architects of the Liberian nation made sure the world spoke of Liberia in the terms of what today is known as a constitutional republic. It was a democracy with parties similar to those in the U.S. at the time: the Republican Party, the True Whig Party, and the National Democratic Party.

Photo: Paul Popper/Getty Images

However, the constitution of 1847 prohibited the native African population from participating in elections by enfranchising only property owners, who were Americo-Liberians. It wasn’t until 1951 that the country allowed universal adult suffrage, although the first native-born to lead the country, Samuel Doe, wouldn’t come until 1980. Americo-Liberians effectively solidified their control over Liberian society by owning much of the means of mass production and distribution of material goods. Economic power was kept within the group through the social relations, business partnerships, and fraternal organizations. They were the minority, but they were the most educated and moneyed class and political power was an inevitable reality. Native Liberians had more menial and supplementary roles with the political economy. If they broke through barriers, they still operated within the grasp of Americo-Liberians. In 1980, the popular yet bloody coup that overthrew Americo-Liberian President William Tolbert, was the culmination of frustrations overlooked by those in power.

In the last 200 years, descendants of the Americo-Liberians have become a distinct ethnic group who make up about 5% of Liberia’s population today. Social evolution in Liberia has largely been an interplay between the peoples who found themselves in the territory after the ACS arrived. Americo-Liberians continue to be viewed as founders of the nation of Liberia as a result of the modernization undertaken by them.

Powered by WPeMatico