Black immigrants in the United States come from diverse backgrounds and regions of the world. Immigrants from African and Caribbean countries make up a majority of the foreign-born population in America. In 2014, Black immigrants made up 8.7% of the 42 million foreign-born population. While they are a growing number of immigrants, their stories are often left out of the immigration narrative. In recent years, stories have come out revealing the horrendous conditions of immigrants in detention centers in the United States. We’ve seen the struggles, the challenges, and the inhumane conditions immigrants face at the border and in the states. What’s been less visible is the role systemic racism plays in the immigration system. That racism impacts Black immigrants the hardest in a number of ways.

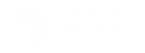

During the COVID-19 pandemic, dozens of families continue to be tragically locked up and separated by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). While there have been many horrific headlines surrounding this topic, one aspect of family detention in 2020 has been grossly underreported. Almost half of the families currently detained by ICE are Haitian. In Karnes County, Texas between January and March of this year, 29% of families detained at the Karnes County Residential Center were Haitian according to tracking by RAICES (The Refugee and Immigration Center for Education and Legal Services). However, as the pandemic progressed and some families were released by ICE, the number of Haitian families detained shockingly rose to 44%. In 2020, the U.S. has consistently detained more Haitian families than any other nationality.

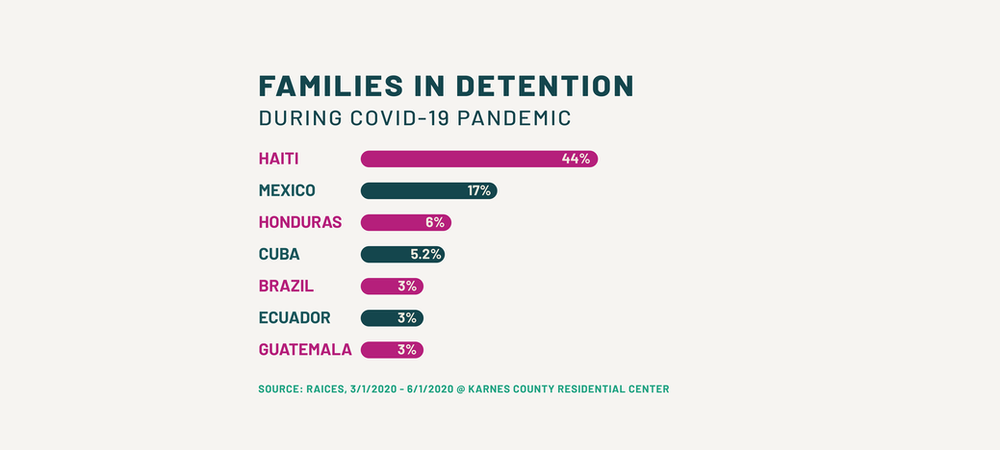

Not only are they detained more often, ICE also makes it more difficult for them to be released. The bond system allows some immigrants to be released from detention if they are able to pay ICE thousands of dollars. RAICES has created a fund dedicated to help immigrants pay for these bonds so they don’t have to remain in detention while an immigration judge reviews their case. The organization’s data of bonds paid by nationality revealed that Haitian immigrants paid significantly higher bonds than other immigrants in detention. Between June 2018 and June 2020, the average bond RAICES paid was $10,500 compared to bonds paid for Haitian immigrants which was $16,700, a 54% increase.

This is not the first time Haitians have experienced the structural and systemic anti-Black racism intertwined in Federal immigration policies and procedures. U.S. immigration policy has consistently and willfully failed to recognize the plight of Haitian migrants. After the devastating 2010 earthquake that took the lives of about 220,000 to 316,000 Haitians, the U.S. suspended deportations, pointing to the need to allow recovery efforts to stabilize the country. Haitians were able to enter the country via humanitarian parole and wait to apply for asylum or receive Temporary Protective Status (TPS) which about 58,000 Haitians were beneficiaries of. Between October 2016 and June 2017, 9,163 Haitians had arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border, with an additional 4,000-6,000 believed to have come from Brazil after migrating there after the earthquake for work. This led the Obama administration to accelerate deportation efforts of those who didn’t have TPS, using expedited removal in 2016.

Making a bad situation worse, the Trump administration set its sight on Haitians in the country via TPS and announced that Haitians no longer qualified for protective status and would lose TPS in July of 2019. This announcement set the stage for the deportation of nearly 60,000 Haitians immigrants back to Haiti. In January 2017, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund legally challenged the Department of Homeland Security’s decision claiming that it was influenced by the administration’s “public hostility towards immigrants of color.”

In a report created by the Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI), interviewees noted that Black immigrant issues become secondary to what is primarily seen as a Latino/Mexican and sometimes secondarily an Asian-American and Pacific Islander issue. The feeling is that because there is a small and spread out population of Black immigrants in the nation, there lacks a large mass to bring attention to Black immigrant issues. As a result, there is a feeling of neglect that is experienced among Black immigrants. This is evident even in mainstream immigrant serving organizations where gaps exist in cultural competency and language accessibility aimed at Black immigrant populations. As a result, accessibility issues lead Black immigrants to not seek out services over fear of future repercussions on their status.

Interviewees also explained how Black immigrants felt left out of the larger conversation on mainstream immigration issues. Key issues like forced family preferences, diversity visa lottery (DV), and temporary protected status were traded away during previous negotiations. These issues all disproportionately impact Black immigrants. In order to push for all immigrants, interviewees suggested immigrant organizations and advocates contend directly with anti-Blackness embedded in movement spaces. Since it is rare for Black immigrant stories to be uplifted, immigration narratives play into the misconception that “black people can’t be immigrants.” Additionally, because of the rampant criminalization of Blackness in America, Black immigrants get caught between the good and bad immigrant binary. The concept of being the “good immigrant” is a phenomenon many if not all immigrants in the U.S. can relate to. Because of race, poverty, and class assumptions, the lived experiences of Black immigrants are commonly inserted into paternalistic charity narratives, like with Haiti, or folded into the realities of Black America.

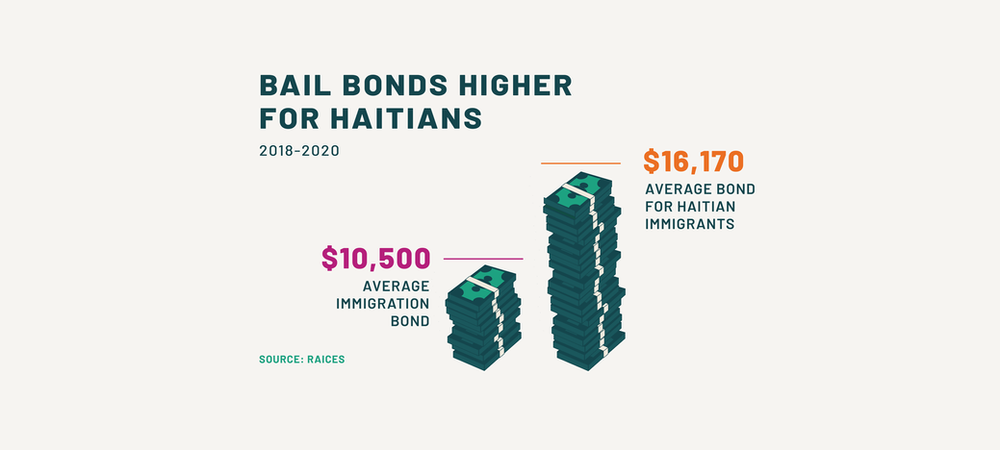

Other issues include policies like the 287(g) program which enables local law enforcement to transfer immigrants they detain to ICE custody. The over-policing of Black people in America means that more Black immigrants end up in the custody of ICE and many are scheduled for deportation over minor offenses. The disparities of Black communities being over-policed throughout the country has inevitably poured into the immigration detention system. Furthermore while in detention, Black immigrants are six times more likely to be sent into solitary confinement. Between 2012 and 2017, immigrants from Africa or the Caribbean made up about 4% of people in ICE detention but made up 24% of all solitary confinement lockups.

While Black immigrants face more obstacles and increasing challenges compared to other groups when it comes to the law, organizations like RAICES and BAJI are amplifying the voices of a population in need. RAICES legal team works with immigrants and asylum seekers to free them from detention and keep families together. Asylum seekers are five times more likely to win their asylum case if they have an attorney. To be a part of the solution, you can partner with organizations like these to learn more and help bring the change you want to see in the immigration system.

Powered by WPeMatico