The Gullah Geechee language is a Creole/English language combined with different African languages. The name Gullah came from the exploitation of their original African tribe. These slaves were descendants of West Africa and took their name from the Gola or Gula tribe in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

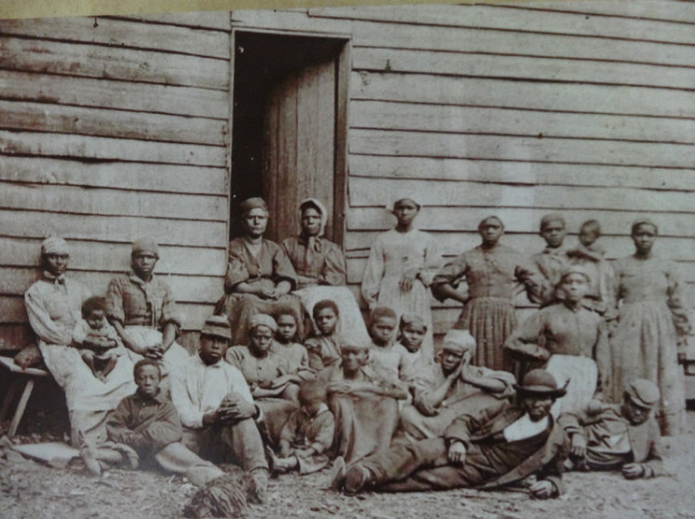

When slaves were brought during the TransAtlantic Slave Trade no one ever thought to care if Africans could understand one another or even the white men that took them. Most Africans didn’t understand each other at all. They were goods and goods only, sold to anyone who would purchase them once they got to America. Most had often been captured in tribal warfare; some had simply been kidnapped to sell to European slave traders. The slave owners preferred slaves from what is nicknamed the “Rice Coast,” a rice-growing region of West Africa.

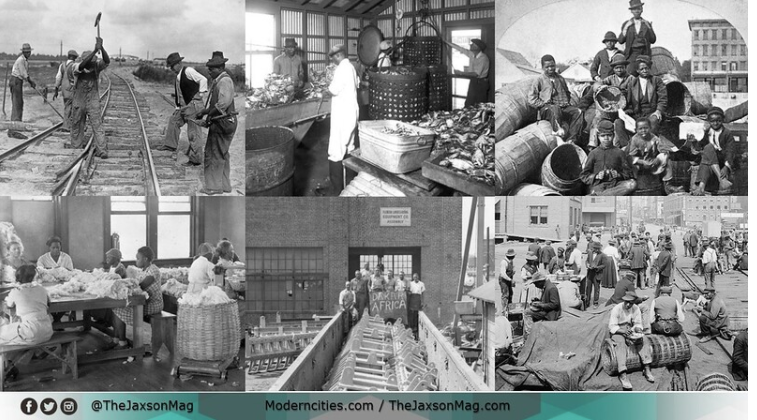

The Gullah, also called Geechees, are descendants of the Africans who were on the rice, indigo and Sea Island cotton plantations of the lower Atlantic coast and most came from the rice-growing regions of West Africa. The word is synonymous with Gullah and means “living by the water.” They literally have their own culture and you not only see it in the language, but in their music, food, and art!

Gullah seems to be used more often by those living in South Carolina, and Geechee for those in Georgia.

It is no surprise that outsiders have perceived the language as slave vernacular or bad English or even Ebonics. We have all heard the constant negative light on Black people not being smart. But really, it was them trying to dumb us down. Our ancestors language of Gullah, was made up of intonations and combinations of English and West African languages, which to me speaks highly of the great intelligence they did have.

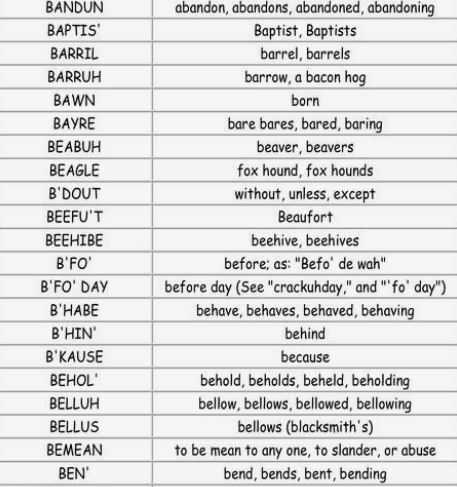

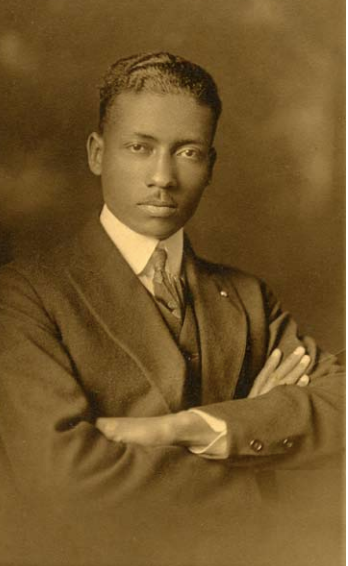

Lorenzo Dow Turner was said to be the founder of this language, or at least the only person who decided to do research on the people of the Sea Islands. In 1932, he initiated a study of the Gullah people that lasted fifteen years. He said that he grew interested when he observed a group of students in his class communicating in a language he didn’t understand. They were the only students in the class that spoke that way. When he asked what it was, they told him they were from the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina.

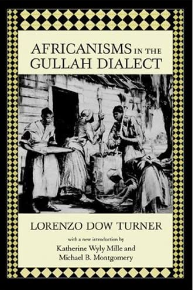

He was absolutely fascinated by this so he traveled up and down the coast interviewing the Gullahs who spoke the language. The vocabulary is the only distinctly, African Creole language in the United States and it has influenced traditional Southern vocabulary and speech patterns. Turner was able to fund his research through the Federal Writers Project which was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelts’ Works Progress Administration. To help he put writers, PhD students, and journalists to work on certain skills and helping to conduct research. Turner published his book Africanisms in the Gullah Dialect (1949) cataloguing over three thousand names and words of West African origin. His book contains several interviews written in the Gullah dialect with an accompanying English translation.

The Gullah are known for preserving more of their African linguistic and cultural heritage than any other African-American community in the United States. How were the Gullah able to even develop their own community and not be messed with by the whites? Well, the white people that were there left because the semi-tropical climate brought diseases like malaria and yellow fever which threatened their lives. They left about 1,200 African slaves behind on the plantations, and these people were able to go back to their African traditions and the Gullahs were able to develop a culture that belonged to them.

During the Civil War, the Union forces arrived on the Sea Islands in 1861 and occupied Beaufort. A lot of Gullahs served with distinction in the Union Army’s First South Carolina Volunteers. Beaufort’s Sea Islands were the first place in the South where slaves were freed. Penn Center, now a Gullah community organization on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, was the very first school for freed slaves. The Gullahs’ isolation from the outside world had increased since the rice planters on the mainland also abandoned their farms and moved away from the area because of labor and flooded lands.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=INLoxvNjFiA

In 2006 the United States Congress passed the “Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Act” that provides $10 million over ten years for the preservation and interpretation of historic sites relating to Gullah culture. The “heritage corridor” extends from southern North Carolina to Northern Florida. The project will be administered by the U.S. National Park Service. The Gullah have become a symbol of cultural pride for Black people throughout the United States, leading up to countless newspaper and magazine articles, documentary films, and books on Gullah culture. There are various cultural festivals such as the Gullah Celebration on Hilton Head Island in February or the Gullah Festival in Beaufort which is held in May.

Mitchelville was a small community created by the Gullah. The government had provided the freedmen with a quarter of an acre of land, and materials to build a small home. Mitchelville lasted from 1862 to 1877, when it finally dissolved once they realized they could move wherever they wanted. Harriet Tubman had even visited Mitchelville, sent to Hilton Head to see the town with her own eyes and share it’s self-governed success.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, the Gullahs traded fruit, vegetables, and wild game on the Simmons family’s property in Spanish Wells. Whatever was left was given to Simmons, who would sail off to Savannah, Georgia once a week to sell the goods. Florida’s earliest plantations were established by the Spanish in the 16th century, long before Europeans took over. They used not only Africans, but Native Americans as well for slave labor.

The Gullah people were also exposed to Christian religious practices in different ways which they added to their African rooted beliefs. These values included belief in a God, community above individuality, respect for elders, kinship bonds and ancestors, respect for nature, and honoring the continuity of life and the afterlife.

Today, the Gullah still stand strong in their community. Since the 1960s, resort development on the Sea Islands has increased property values resulting in constant development pressure, and the gentrification continues to threaten the Gullah way of life. Although the land was passed down from generation to generation, a lot of the children who did own shares of land got married and moved away to get better jobs. The ones who did stay, struggle with paying ever increasing property taxes and because of shared ownership, a lot of Gullah people can’t even get mortgages to build homes on their property. Because they can’t afford to pay cash, they just buy trailers (which are taxed as personal property, not houses).

The Gullah have also struggled to preserve their traditional culture in the face of much more contact with modern culture and media. The Gullah also reached out to West Africa and had three celebrated “homecomings” to Sierra Leone in 1989,1997, and 2005 where many of the Gullahs’ ancestors originated.

These homecomings brought the filming of three documentaries, Family Across the Sea (1990), The Language You Cry In (1998), and Priscilla’s Homecoming (in production). The American Bible Society published De New Testament in 2005. In November 2011, Healin fa de Soul, a five-CD collection of stories from the Gullah Bible was released. This collection includes Scipcha Wa De Bring Healing (“Scripture That Heals”) and the Gospel of John (De Good Nyews Bout Jedus Christ Wa John Write). The recordings helped people develop an interest in the culture.

I believe that as we continue on in the years to come we will hear more of the Gullah culture and our people will embrace and learn more about it; might even start speaking the Gullah language amongst each other. One thing about our culture as Black people is that we know how to preserve our traditions and fight for our right to stay authentic to ourselves and our heritage.